An olive harvest: Olive oil tasting

4. Sunday

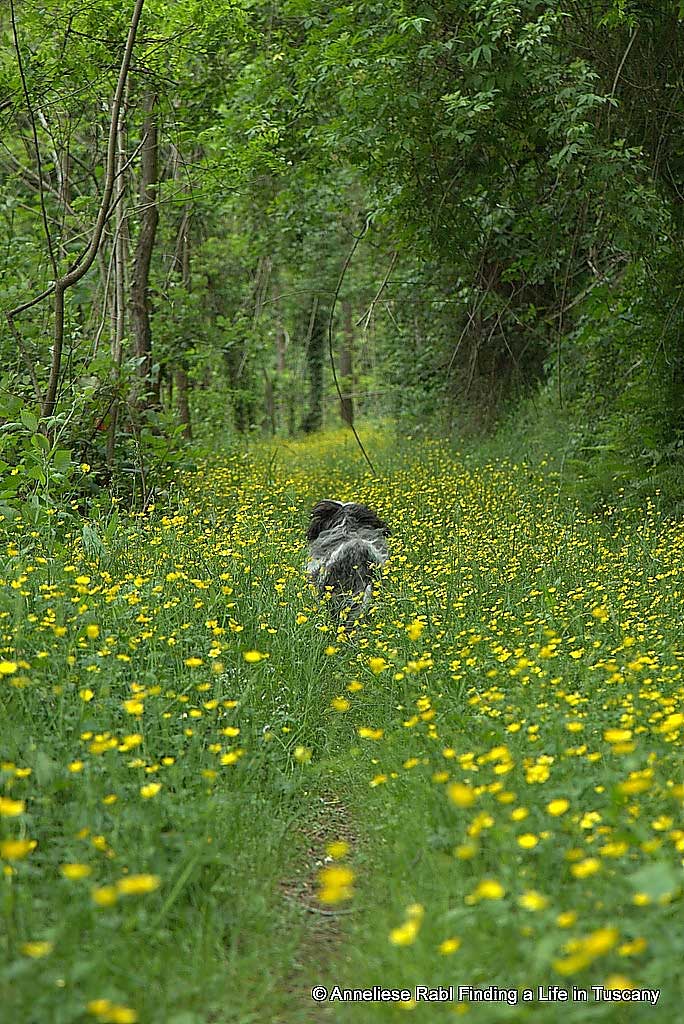

Fortune is on our side. It is raining and no olives can be harvested. Of course, we are not lucky thanks to this unexpected day off, but rather because today a small town nearby has organized a tasting in an oil mill and since it is raining we can participate. Fantastic!

On our arrival, there are several spectators, listeners and complete non-professionals eager to learn. On the horseshoe shaped table stand plastic cups, slices of peeled apples (what for we wonder) and a fair quantity of olive oil bottles. Good luck is really on our side. The friendly looking man in front of us is an authentic olive oil expert. The tasting technique can differ from examiner to examiner. In any case, however, it is publicly regulated by the laws in force today.

The skilled teacher explains to us complete beginners in broad outlines what he is going to show us. Our starting point is not the best. Before the tasting we should not have used strong perfume, soap or other cosmetics with a persistent scent. Neither should we have smoked for at least thirty minutes or eaten for an hour. Furthermore, our physiological and psychological condition has to be satisfactory, which they are, I think. All this in order not to influence the thorough assessment of the olive oils and the final verdict.

Quality and defect of the oil depend on various factors:

- geographical production area

- climatic conditions

- ripeness of the olives

- treatment of the trees and the soil

- harvesting technology

- storage of the olives

- mixing time of the crushed olives and temperature during processing

- extraction method

- storage of the finished oil

- hygiene and general cleanliness

A real specialist examines the oil against the light. Then he shakes the contents of the bottle slightly to test its fluidity. Our connoisseur, who has in front of him a group of people full of good will but nothing else, decides to pour a small quantity – about one tablespoon – into cups set up in front of him. Those near him distribute them among the participants until the last row is reached and everybody has a cup in his hands. A professional tasting glass, of course, is not as ours of plastic but of glass. The colour is dark blue or brown. In this way the person who tastes cannot see the colour of the oil, which could be deceptive.

He invites us to observe the fluidity and the fragrance of the oil and to describe our impressions. In order to encourage the evaporation of the aromatic compounds we warm the cup in the palm of our hands. Then we look at each other a little embarrassed. The fact is that we are not sure about our sensations. Some seem to have no opinion at all, others are too shy to express themselves. Many are totally concentrated on smelling, trying to hide their embarrassment and hoping that someone else will speak first. Then there are those who summon up all their courage but do not find the right words. There are, in fact, specific expressions we are absolutely not acquainted with.

Our expert talks about “fruity”, “almond like”, “lively”, “pungent”, even “grassy” scents. Wow! We look at each other and learn that there are actually oils with a specific smell, resembling freshly cut grass. “Fruity” describes the odour of olives in perfect shape harvested at the right moment. (Right moment..?) “Almond like” refers principally to the fragrance of fresh almonds. Sometimes, instead, it is connected with the dried ones, the smell of which can easily be mixed up with almonds becoming rancid. “Lively” is the correct word to describe new oil, which releases long-lasting, pleasant, aromatic flavours. A good, fruity oil from the new crop is called “pungent”. For us a totally new world, but we are ready to learn.

Now he shows us how to slurp a small quantity of oil by sipping first slow and lightly and then stronger. In this way it spreads into the whole oral cavity allowing a close contact between the oil and the sensors of mouth and nose. He advises us to let the mouth rest for a brief moment. We must press the tongue slowly and slightly against the palate. Finally we had to inhale air again, abruptly and with half opened lips. The last movements need to be repeated several times. Before spitting the oil out, we must keep it in our mouths for at least twenty seconds.

Equally important is that we continue to move our tongues in order to thoroughly assess the aftertaste trying to remember as many flavours and fragrances as possible. Again he invites us to describe our sensations. From the little crowd in front of him we hear a courageous “fresh”, “has a nice taste” and “pleasant”. The words, obviously, have little or nothing to do with the vocabulary used by our expert. He clearly does not understand us because we do not speak the same language.

It’s no good wanting to learn too many things at once and, objectively, we do not have much time. Otherwise he would have told us for instance, that olive oils are divided into “fruity sweet” and “fruity green”. They mainly depend on the type, or cultivar, the ripeness of the olives and the production area. Next year we will certainly have the opportunity to deepen our knowledge.

Now he explains that “bitter” refers to the typical taste of oil from green or pink-violet olives. According to its intensity it can be more or less pleasant. “Sour” oil produces a binding effect. “Sweet” does not mean that it is sugary, but that it has neither pronounced bitter nor astringent or piquant properties. “Artichoke” expresses a particularly pleasant, mainly new oil. Frost damaged olives have a “frozen” taste that is to say a very weak thin-bodied, tending to a dry and wooden flavour. “Dry” refers to an oil from drupes which ripened during a prolonged period of aridity. “Astringent” describes an oil from unripe olives, particularly rich in polyphenols. The sensation, while tasting it, is like biting into an unripe fruit. If the oil tastes of “net” it has a peculiar rubbery flavour tending to dry attributable to the fact that the drupes were left for too long on the catching nets. Then he talks about flavours described as “winy-vinegary”, “rancid”, “muddy”, “musty”, “metallic”, “wicker”, “vegetation water” and “blurry”. Our heads are spinning! Although we are fully concentrated on what he is explaining, it is not easy to follow him.

During the whole time we continue to taste different oils. Between one sip and another we are recommended to eat a piece of apple (that’s what they are needed for!). This because apples neutralize the taste in the mouth permitting to continue the tasting. After each test our expert asks for our impressions. Fortunately he is good to us because he nearly always puts the right words into our mouths. When he remains in silence and waits for an answer from our side it is clear that we are genuine beginners. On the other hand it is not easy to familiarize with the different qualities and the terminology of the experts. The tasting has to be learned and requires time and patience.

At the end of the lesson we are completely satisfied. We know more than before and feel – at least a little – like real olive oil experts.

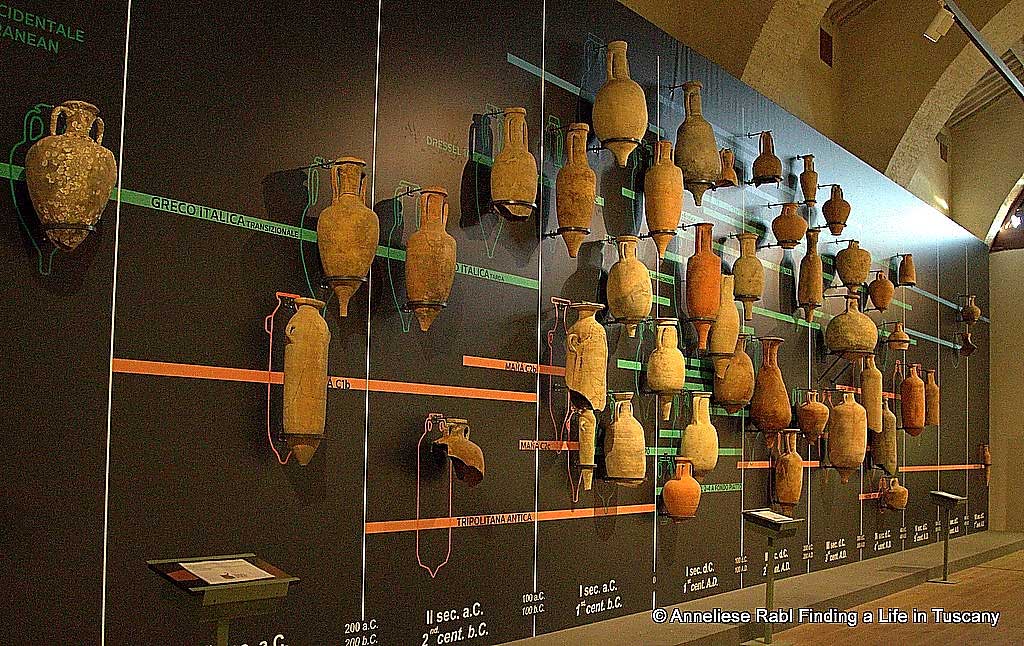

(Front page image: Vivere e lavorare in campagna, Edizione del Baldo, Verona 2015)

Leave a Reply