An olive harvest: History of the olive

2. Sunday

A week has passed and I have recovered from last Sunday’s hard work. At least that’s what I thought but when bending the upper part of my body forwards, my left hand moves automatically towards my back and my face shows a painful expression belying my words.

According to the weather forecast we should have a nice day. Therefore I arrive early at the campo to continue the harvest. I know what I have to do. Obviously gather the olives, which have fallen from the trees, allowing the pickers to later spread the nets under them. Factories or owners of olive groves with hundreds or thousands of trees would definitely leave them where they. However who, like the owner of the campo, can call his own only thirty or forty trees and does not want to press his olives mixed with those of other small olive groves counts on every single olive, as long as it is in an acceptable state.

Let me say just once that olives picked one by one, in this uncomfortable position on my knees, is an ungrateful job. Besides, it takes a lot of time and energy for meagre spoils. After half a day’s busy work, hardly half a basket is filled. I notice that nobody comes too close. Could it be because they fear that I may ask them to lend me a hand? In any case it gives me time to be lost in thought.

This week I met a friend of mine, a Tuscan lady, proud exactly like the pickers in the olive grove. She knew about my intention to participate at an olive harvest. With an amused air she listened to what I had to say about the first day. Then she asked me: “Did you know that the olive tree is very, very old?”

“Yes. I have read that long before Jesus’ birth people have gathered and pressed oil from olives using hand-operated mills. Interestingly nobody knows when its cultivation actually started. The tree probably originates from Asia Minor whereas its cultivation started in Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq) and South Anatolia (today’s Turkey). Thanks to the Phoenicians and the citizens of Carthage, it spread to Iran, Syria and Palestine and the remaining Mediterranean countries, including Italy.”

“That’s right”, answered the lady and continued: “The demand for olive oil increased constantly and greatly favoured the development and the prosperity of the coastal areas, where the cultivation of the olive tree was possible. By the way, in former times, it was commonly known that it could grow only within a distance of three hundred stadiums from the sea (a stadium corresponds to about one hundred and eighty meters). Ebla was one of the most important centres of the caravan routes. There, people traded fabrics, bronze objects and other merchandises for wine and olive oil.

It was, in fact, essential not only as food and fuel for lamps but was also needed for religious ceremonies. Prior to the Greek and the Roman era, olive twigs were found in the tombs of Egyptian Pharaohs. It is known that this ancient population used olive oil for beauty care, personal hygiene and medicines.”

The Tuscan lady knows exactly what she is talking about. Doubtlessly, the passionate way of talking reveals her love of history – and olive oil. Of course.

“Medicine was prepared in quite an unusual way, underlining the strong connection between medical art and magic. After having visited the patient and diagnosed the malady the physician would write a magic formula on a piece of papyrus. He would use special ink, powerful enough to drive the bad spirit, responsible for the illness, out of the patient’s body. Then, he would dip the papyrus into olive oil until the ink completely dissolved. At this point the patient, as a cure, would drink it. Both, the physician and the patient, would hope in a quick recovery. Besides, in the Egyptian world the tree represented fertility and life.”

“And what happened in Greece and in Rome?” She had indeed aroused my curiosity.

“Since Athena’s victory over Poseidon, the tree was considered holy by the ancient Greeks. The winners of the Panathenaic celebrations, athletic and musical contests, were awarded with Panathenaic amphoras. They were big, bulgy clay jars with two handles and decorated with black figures containing the precious olive oil. They could either keep or, being much in demand, sell at outrageously high prices.

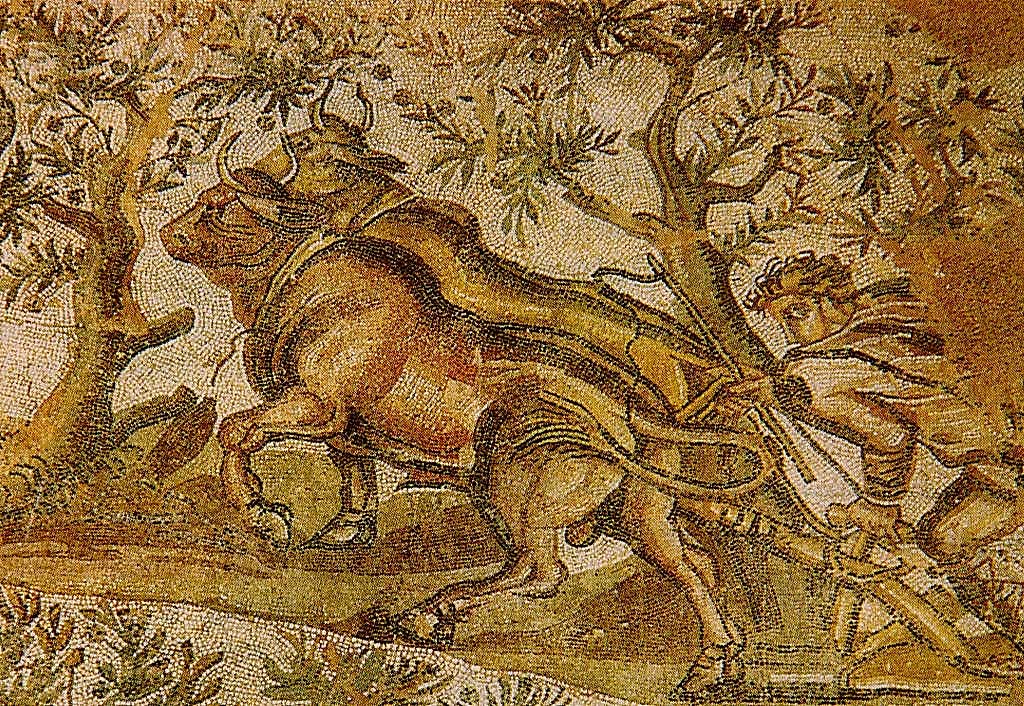

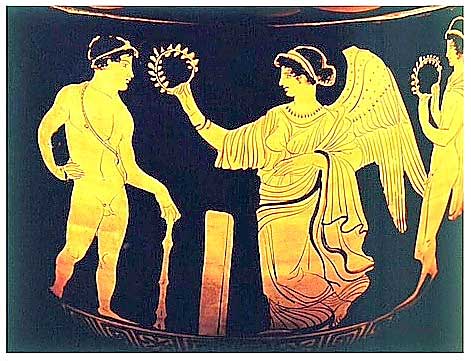

The tree played an important role in other competitions, too. The winners of the Olympic games, in fact, were crowned with wreaths of olive leaves. Afterwards a dancing procession accompanied them to a banquet, where they were offered meat from a sacrificed bull. On the way the crowd applauded and covered the athletes with olive leaves. This in accordance with a very old rite of good will, called phyllobolìa, or throwing of the leaves.

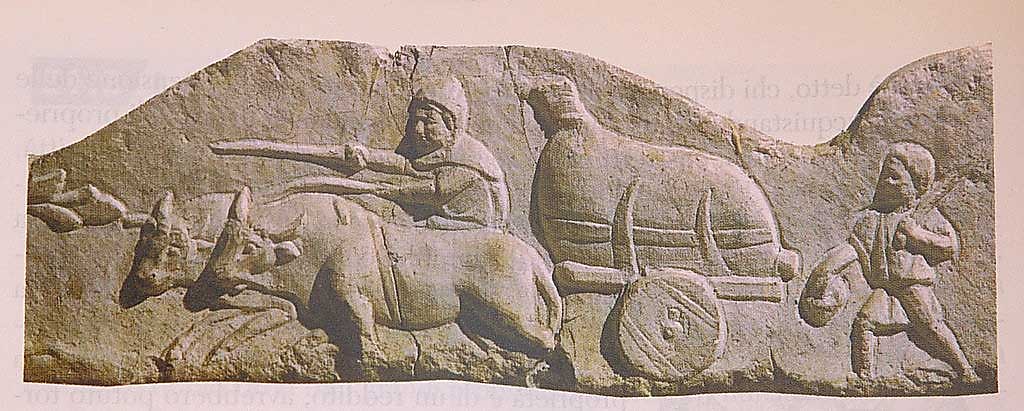

In ancient Rome the olive tree was a sign of peace and prosperity. During the festivities of the turn of the year it was custom to offer olive twigs while wishing wealth and happiness. The oil was imported from the South of France, Spain, North Africa, Palestine, Cyprus and Greece. Together with wheat and dried or salted fish it became one of the most important merchandises for food exchange. Without this precious product, Rome would have had serious difficulties in feeding the one million inhabitants of those times.

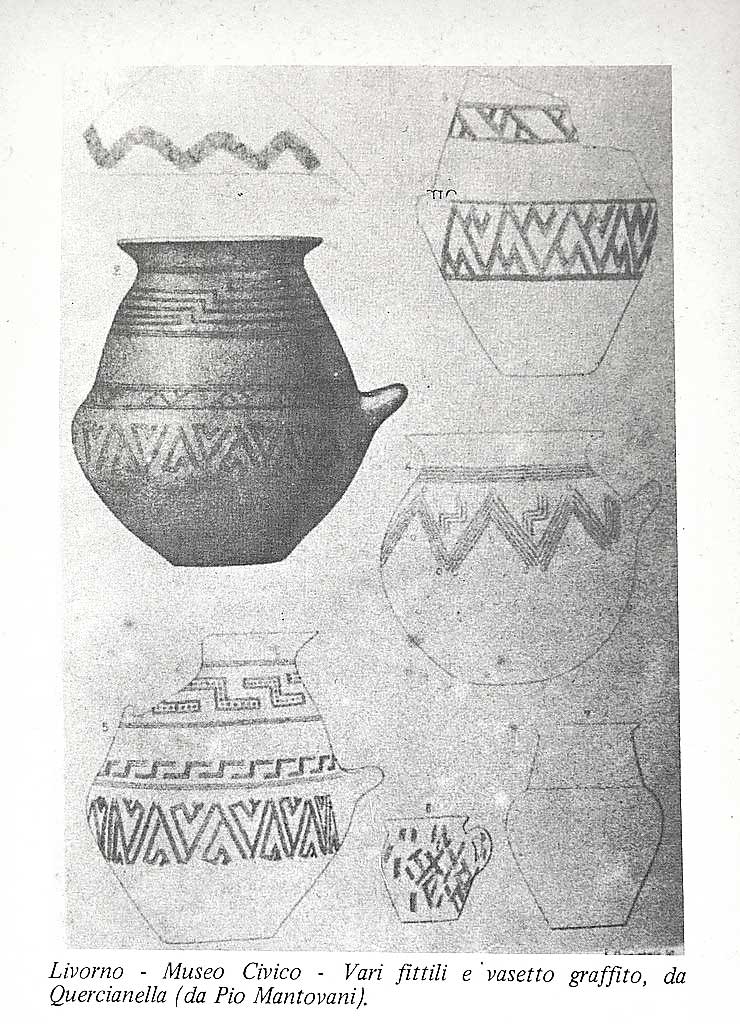

If we had lived 2000 years ago the situation on the campo would have been completely different. To start with we would have picked the olives in different moments. We would have obtained oleum ex albis olivis, oleum viride, oleum maturum and oleum caducum. The latter, made of the worst olives, served for the pressing of the oil destined to feed the slaves.

There would have been ladders, different sized baskets and bushels, a special measure used for grain and olives. Ropes made of hemp and broom, iron cups to draw the oil, big and small sponges. Lids to close the oil pots and special jars for the transport of the oil. Last but not least reed mats on which to distribute the olives.

Previously, someone would have already piled up a fair quantity of firewood, essential for the different operations. We would have picked the olives by hand on a fine day and then distributed them on the reed mats to be sifted and cleaned. A part would have immediately been taken to the oil press. The remaining drupes would have been transformed directly there, on the campo, into brined olives, perfect for important occasions, as an expert of that time explains:

“… cover the bottom of an oil jar with a bed of dried fennel leaves. Fill with olives mixed with seeds of lentisk (Pistacia lentiscus) and fennel. As soon as you reach the top of the jar, cover with strong brine. Press the olives with a top layer of reed leaves, so they remain immersed under the liquid. If necessary pour strong brine over them again until you reach the very top of the jar. Olives prepared in this way are not too good just as they are, but are perfect for any dish usually served at luxury lunches. When needed they are taken from the jar and crushed and are ready to receive any desired dressing. Usually, however, after having been crushed, they are mixed with chives, rue (Ruta graveolens) and mint, finely chopped with tender celery. Add a drop of vinegar, season with pepper and little honey or honeyed wine and a ‘generous helping of green olive oil. Cover with a bunch of green celery.”

(Columella, 4-ca. 70) De re rustica – Lib. XII, cap. XLIX, Different ways to dress and to preserve green olives)

There is, however, another fundamental difference between today and 2000 years ago. While you choose to take part of this harvest, in earlier days it was put into the hands of the slaves as part of their ordinary duties. The only qualification these mediastini needed was to endure fatigue. In fact, whereas specific intellectual and manual capability was required for supervising the cattle, threshing the grain, harvesting and pressing the grapes, the olive crop could be managed by mediocre slaves, provided with youth, agile limbs, flexible muscles and an eyesight acute enough so as not to leave not too many olives on the trees. All of which you seem not to be short of either…“

Leave a Reply